“Originality is fragile. You have to love and protect your ugly babies, your early creative projects and original ideas.” – Ed Catmull, Pixar co-founder and former president of Walt Disney Animation Studios

Because of Pixar’s highly successful track record emotionally resonant and commercially successful films, Ed Catmull observes that many people assume Pixar films are born being resonant, striking, and meaningful. But as he explains in his book “Creativity, Inc.”, all Pixar films are born as ugly babies. “The early reels of all Pixar films are pretty ugly. Their potential glimmers. But what is most striking is their flaws.”

Directors Andrew Stanton and Lee Unkrich did not create the versions of “Finding Nemo” and “Coco” that Pixar fans know and love today on the first try… not even close. Director Pete Docter was afraid he was going to get fired because the story concept of what became “Inside Out” simply wasn’t working, and he didn’t know how to fix it.

Pixar is not the only successful franchise to go through the the ‘ugly baby’ growing pains. One of the most famous babies in the world – “Baby Yoda” from the “The Mandalorian” series – started out really ugly.

Something truly original and creative is always a risk.

Catmull says an infant project’s potential can be hard to judge at the early stages. Potential can be shy to reveal itself in baby projects that start life really ugly. Projects that are as pink and perfect as the Gerber baby can have strong initial promise but fail to realize their perceived potential.

Pixar spent years developing a film about an endangered lizard raised in a lab which they were certain would be a big hit. After several years of trying and failing to make the story work, Catmull reports that Pixar eventually decided to shelve the entire project despite years of significant artistic and financial investment.

How does Pixar know the difference between baby projects that will mature into successful films and those that fail go the distance?

They don’t…

Pixar nurtures their baby projects by assigning teams of directors, writers, and concept artists to develop a story idea and the film’s potential look and feel. Once a baby project is sufficiently developed to the toddler stage, the directors pitch it during one of Pixar’s “brain trust” meetings, a gathering of Pixar’s top directors, writers, creatives, and executives who offer feedback and suggestions.

Before the brain trust decides to green light a baby project into production or not – a huge investment of Pixar’s creative and financial resources – the baby is given time and support to develop its potential. The brain trust tracks the baby’s development and after each meeting, and decides to either keep investing in the baby’s growth or re-assign the development team to nurture other potential projects with more promise.

Creativity needs support, investment, and … … … … time.

Some of your early creative projects will fail to mature and gain strength and you’ll have to put them to rest. Try not to beat yourself up about this natural selection process. It happens all the time, even to the pros at Pixar. Thank the baby for its contribution and thank yourself for the valuable experience you gained in learning how to nurture your creativity.

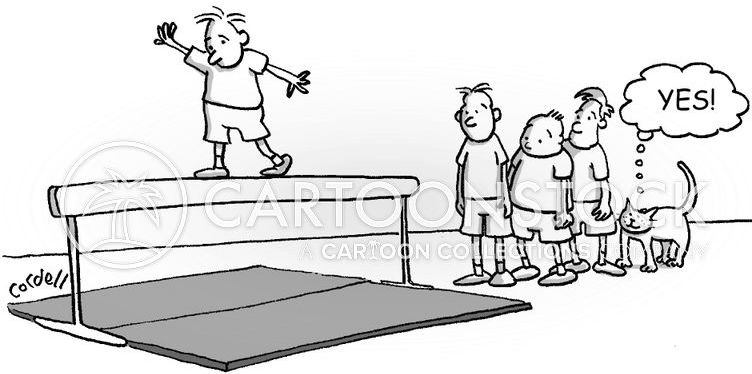

Don’t pit your middle-schooler against someone else’s Olympian

Our analytic brain frequently sabotages our creativity because it’s impossible not to compare our baby project with someone else’s magnus opus. After such a comparison, it seems inevitable that our baby will never grow into beautiful maturity. Despair and child abandonment soon follow.

According to Catmull, that’s an unfair comparison to make. “It’s the creative equivalent of pitting a middle-schooler against an Olympic-level athlete.”

Taken a step further, we can then leap to the dead-end conclusion that we simply don’t have the talent to ever produce something that is as meaningful and resonant as the works of artists we admire.

Here’s what’s really happening:

“You’re trying to do a triple backflip in a gale force wind… and you’re mad at yourself for not sticking the landing. It’s amazing you’re still alive.” – Brad Bird to Pete Docter during a Pixar brain trust meeting for “Inside Out”

The Harry Potter Problem

Stories of creativity striking like lightning abound in our talent-obssesed culture. One of the most famous examples is J.K. Rowling coming up with the idea for the Harry Potter series during a delayed train ride and immediately starting to write the first novel that same day.

While these events are true according to Rowling, if taken at face-value, her enviable experience of having a fully developed premise and fantasy world fall into her lap creates a misleading impression. It feeds the attractive illusion that truly talented creative minds get it right on the first try, without struggle or failure.

I call this…

The Salieri Complex

Focusing solely on the moment of inspiration and ignoring the years of development and hard work required to elevate an inspired idea into a finished work of art creates the illusion of overnight success.

It also perpetuates the myth that real geniuses get it perfect without any struggle or self-doubt, as a jealous rival composer Salieri observes of Mozart in the film “Amadeus”.

“These were first and only drafts of music. But they showed no corrections of any kind… He had simply written down music already finished… in his head. Page after page of it. As if he was just taking dictation.” – “Amadeus”, screenplay by Peter Shaffer

There is an epilogue to the Harry Potter inspiration story that doesn’t get much press. According to The Friendly Editor, Rowling rewrote the first chapter of the first book so many times that that her early attempts “bear no resemblance to anything in the finished book.”

Whatever she may claim after the fact, proof exists that even Rowling didn’t have it all figured out in one train ride. In pages of Rowling’s early drafts published in “Harry Potter: A Journey Through a History of Magic”, Voldemort is a little, red-eyed dwarf, and Mr. Dursley has a conversation with the minister of magic about what to do with baby Harry.

“An overnight success 10 years in the making.”

The math in Tom Clancy‘s quote above applies to the Harry Potter series. Rowling wrote multiple books she never attempted to get published before Harry Potter. It took her more than 15 drafts to sculpt the published version of the now famous first chapter ‘The Boy Who Lived’. She spent over 6 years planning the series and creating the wizarding world before she completed a first draft of the first book.

Rowling invested almost 20 years of her life to create the Harry Potter series. Whatever Salieri may believe, she did not take dictation from a creative muse that tapped her for greatness – duck-duck-goose style – on the 11:00 train from Manchester to London.

A similar mystique surrounds Stephenie Meyer. She had a dream that gave her the idea for the Twilight series and wrote the first draft in three months, having never written anything before, while caring for three small children. Like Rowling’s story, these events are true according to Meyer. But the often-intimidated-but-never-duplicated success of the Twilight series makes Meyer the exception that proves the rule.

It takes more than inspiration

Young creatives struggling with their first projects can fall into the following trap: “My work isn’t an instant success, so inspiration must be the problem.”

Or even worse: “I executed my most inspired idea and it still failed. That proves I don’t have any good ideas.”

Our initial inspiration will probably fail to measure up to the lightning-strike stories associated with Rowling and Meyer. Our first drafts will probably be weak and confused and fall short of the first-try perfection Salieri attributed to Mozart.

Take it from Ed Catmull and the Pixar brain trust on how the creative process really plays out. “A basic truth: people who take on complicated creative projects become lost at some point in the process.”

Struggle and self-doubt are inevitable… and a normal part of the creative process.

When you’re ready to throw your baby project out with the bathwater, remember the nurturing support and patience of the Pixar brain trust. Remember the 6 years of development that Rowling invested in Harry Potter before she published the first book. Remember that Mozart was trained from infancy by his domineering, professional musician father who invested all of the family’s resources in his son at the expense of his potentially equally talented daughter.

Give yourself and your creative baby a realistic chance to develop. Be prepared for ugly cries, snot, and sleepless nights. Every Olympian started out in diapers.

Leave a Reply