Magic System Spectrum

What sets fantasy apart from all stories is magic.

Using Brandon Sanderson‘s ‘Laws of Magic‘ as a framework, the magic systems in popular fantasy fiction fall on a spectrum from ‘hard’ to ‘soft’.

In this series we’ll delve into the hard magic of ‘Avatar: The Last Airbender‘ the TV series, the firm magic of the Harry Potter, including analysis of both novels and the film series, and the soft magic of Lord of the Rings.

We’ll look at what qualities of a magic system determine where it lies on the spectrum, and how the authors used each type of magic to enhance their storytelling.

Hard Magic Systems

Hard magic systems follow strict rules and function like science. The use of this type of magic by characters in the story is usually controlled and consistent. Hard magic systems are the easiest to codify thanks to their clearly defined scope, consequences, limitations, and costs that govern what the magic can and can’t do within the storyworld.

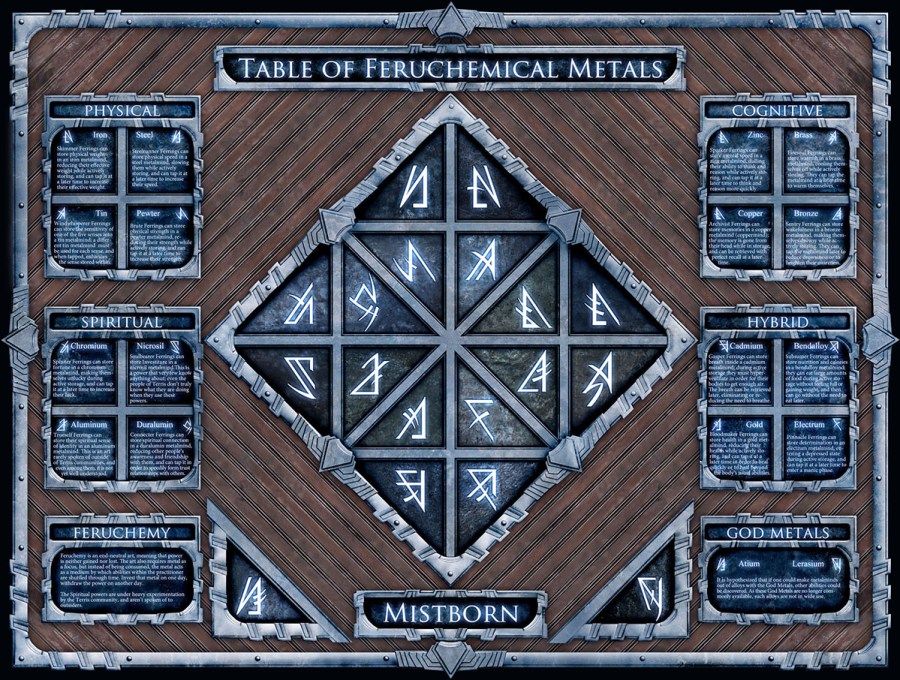

Brandon Sanderson explains the rules of how the his magic systems works to his readers in detail. A prolific author and expert architect of hard magic systems, Sanderson sometimes goes as far to explain the mechanics behind how the magic actually works, such as in his ‘Mistborn’ series.

Hard Magic in ‘Avatar: The Last Airbender’

In Michael DiMartino and Bryan Konietzko’s animated television series ‘Avatar: The Last Airbender’, the magic system is the telekinetic manipulation – called ‘bending’ – of the four elements of earth, wind, water, and fire.

The rules of bending are straightforward:

- Except for the avatar, benders can only manipulate one of the four elements.

- The ability to bend is innate (e.g. Katara was born a waterbender but her brother Soka was not), and determined by which nation a character is born into. (e.g. all waterbenders are born into a Water Tribe).

- Bending is a skill acquired through study and discipline.

- Bending is achieved through physical movements and gestures based on Chinese martial arts, and each element requires a different style of movement.

In ‘Avatar’, bending is a hard magic system because use of the magic largely conforms to the four pre-established rules above.

The concept of bending is a defining characteristic of the central characters and drives the narrative of ‘Avatar’. This places the magic system at the root of the central conflict of the story. Because of this vital narrative role of the magic system, DiMartino and Konietzko knew the audience needs to understand how bending works so they could follow the story and understand the motivations and choices of the characters. The writers provide this crucial information in the prologue which begins each episode. The principles of the elemental magic system are introduced, and the avatar’s extra bending abilities are explained as central to his/her role in restoring balance to the storyworld. The prologue also establishes the stakes: the avatar has disappeared and the storyworld has fallen out of balance as a consequence. The powerful Fire Nation is attacking other nations, demonstrating the urgent need for the avatar’s return.

Bend But Don’t Break

‘Avatar’ pushes the boundaries of its hard magic system, but it doesn’t break its own rules. Bending isn’t mysterious or full of major twists in terms of how the magic works.

Occasionally there is a new bending style or extension about what the bending magic is capable of. But these new add-ons are logical and grounded in the magic that has come before. (e.g. Aang’s avatar state and ability to spirit bend, the extension of firebending to lightning, waterbending to bloodbending, and earthbending to lavabending).

The writers use two methods to make the extensions of their magic system credible. They mostly follow their own pre-existing rules which the audience has already learned. And their use foreshadowing is both skillful and organic to the plot. (e.g. Katara sees bloodbending before she actually performs it herself in order to escape.) This culminates in the audience learning and accepting new extensions of the magic system in an easeful way that is both logical and doesn’t take them out of the story.

Harder Magic in ‘Mistborn’

Because the rules that control magic in Brandon Sanderson’s ‘Mistborn‘ series are more strict and prescriptive than ‘Avatar’, it’s magic system is harder.

In Mistborn, telekinesis magic only works on objects the character would be able to physically lift themselves. This key characteristic is based on the laws of physics rather than the more fluid concept of the natural elements.

Because there isn’t an unbreakable, scientifically-determined limit on the amount of an element that a bender can move in ‘Avatar’, its magic system is softer than ‘Mistborn’s’. Benders are limited in the amount of an element they can bend, but this limitation comes from the softer aspects of the magic system (i.e. an individual bender’s skill level and confidence).

Very Hard Magic in ‘FullMetal Alchemist’

The magic in Hiromu Arakawa’s Japanese magna series ‘Fullmetal Alchemist: Brotherhood’ is harder than both ‘Avatar’ and ‘Mistborn’ because the rules are so precise they create a formula.

Arakawa’s magic system is based on alchemy and is governed by alchemy’s law of equivalent exchange: “It is impossible to create something out of the nothing. If one wishes to obtain, then something of equal value must be given.” Although the laws of alchemy are not a true science like the laws of physics, Arakawa’s use of the principle in ‘Fullmetal’ creates a harder magic system than ‘Mistborn’.

Arakawa has a character in ‘Fullmetal’ assemble a radio from a pile of pieces with magic. But all the pieces were there to begin with – none where created out of thin air. But a firebender can conjure fire out of thin air, making ‘Avatar’s magic softer than ‘Fullmetal’s’.

Storytelling with Hard Magic Systems

Authors writing with hard magic systems must follow their own rules the most closely, otherwise their stories will lack internal consistency. Hard magic also imposes limits on a writer’s storytelling options since there are more rules to consider when using the magic to tell the story and develop the characters.

Because the rules of a hard magic system are so specific to the narrative, writers need clearly explain the rules to audiences so they can follow the story without confusion. Hence the explanatory prologue that appears before every episode of both ‘Avatar’ and ‘Fullmetal’.

However, since hard magic is explained so thoroughly for plot purposes, it becomes more difficult for writers to maintain their magic’s sense of mystery and surprise.

With a very hard magic system like ‘Fullmetal’, audiences know – and even can reliably predict – what the characters can and can’t do with a hard magic system in any given circumstance. This taxes the writers to pull off genuine surprises and twists without breaking their own rules.

A common way writers stay a step ahead of their audiences is by withholding crucial information about the magic system from their characters, and thus from the audience. But the harder the magic system is, the more predictable it is. Therefore the more difficult withholding information without breaking the rules becomes.

‘Avatar’ For The Win

The writers of ‘Avatar’ address this problem of predictability by rooting their story deeply in the character arcs of Aang and Prince Zuko, rather than the capabilities of the magic system. DiMartino and Konietzko excel at balancing character development with their magic system, resulting in bending that is superbly integrated into the character arcs of ‘Avatar’s’ well-designed cast.

This smart approach takes the burden of keeping the plot moving forward off the magic system. It also keeps the audience – which may lose interest once they can predict how magic will be used in the story’s climax – engaged with ‘Avatar’s’ emotionally compelling characters.

Dune – The Soft Magic of ‘Spice’

Magic systems also feature heavily in science fiction, fantasy’s cousin. Magic is what qualifies both genres as ‘speculative fiction’ and is often a highly distinctive narrative element. While fantasy unabashedly uses outright magic, science fiction usually features an magical element which is presented as an advanced form of futuristic science. Because of this trademark of the genre, there is a a perception that science fiction authors prefer hard magic systems since a highly structured magic system is easier for readers to accept as advanced science.

But magic systems transcend genre. The magic system of science fiction, fantasy, dystopian fiction (e.g. Hunger Games, Divergent), and even outliers such as paranormal romance (Twilight) can fall anywhere on the magic system spectrum.

Frank Herbert’s ‘Dune‘ is classified as science fiction, but the enhanced abilities produced in humans by ‘spice’ are soft magic. Like J.R.R. Tolkien, who does not explain how the magic of the one ring in ‘Lord of the Rings’ works, Herbert doesn’t explain how spice works. Readers must simply believe that spice is a powerful hallucinogen that extends human vitality and lifespan and enables interstellar space travel without knowing the rules of Herbert’s mysterious magic system.

Unlike Tolkien who describes how and why the one ring was forged, Herbert doesn’t explain how or why ‘spice’ comes from the giant sand worms of Arrakis. Likewise, readers don’t initially understand why Paul is more sensitive to spice than other humans or how he endures the acute psychological pain of the gom jabbar test. Similar to Dumbledore’s conversations with Harry Potter at the end of ‘Philosopher’s Stone’, Herbert only reveals pieces of the answers – Paul’s carefully designed genealogy, curated by the Bene Gesserit – after the fact. Because of these unexplained effects of spice and Paul’s unique gifts, Herbert’s magic system is soft since there are no reliable rules.

Unlike magic in ‘Avatar’ and ‘Harry Potter’, how spice works isn’t important to the plot of ‘Dune’. Instead Herbert’s excellent geopolitical world building takes center stage. Rather than focusing on the magic of spice itself, Herbert creates a detailed and complex ecosystem around spice to fuel the conflict between the House Atreides and House Harkonnen to drive his plot. What makes ‘Dune’ science fiction rather than fantasy is that Herbert uses the intense geopolitical conflict around the magic system of spice as the framework for Paul’s character arc and the plot.

Pros and Cons of Writing with Hard Magic

How effectively a writer uses magic – no matter how hard or soft – to tell their story varies widely, and isn’t dictated by where the magic falls on the spectrum. Soft magic can be used to tell a science fiction story, as in ‘Dune’, ‘Star Wars’, and ‘Hunger Games’. Hard magic can be used to tell a fantasy story, as in ‘Avatar’ and ‘Mistborn’. Firm magic can be used to tell a high fantasy story such as ‘Harry Potter’, a futuristic dystopia such as ‘Divergent’, to a paranormal romance such as ‘Twilight’.

More Posts In This Series

Part 2 – ‘Harry Potter’ – Firm Magic Systems

Part 3 – ‘Patronus & Dementor” – Emotion Based Magic Systems

Part 4 – ‘Harry Potter’ – Hybrid Magic Systems

Part 5 – ‘Lord of the Rings’ – Soft Magic Systems

Which do you enjoy reading more – soft or hard magic systems? Tell me why in the comments!

Great content, thanks for sharing

Hi Kelvin, thanks very much and I’m so glad enjoyed this post. I hope you also read and enjoyed the rest of the posts in my magic systems series.